-

- Introduction

- What is culture?

- Culture is like an Iceberg

- Culture and its core elements

- What is intercultural communication?

- Which are the challenges in intercultural communication?

- Transnational communication skills

- Enhancing cultural awareness for transnational communication

- Choosing adequate communication strategies

- Intercultural Conflict Management

- Stumbling blocks in Intercultural Communication

- Which are the elements that may lead to a conflict situation?

- Conflict strategies

- Conflict prevention

- Working on the intercultural image of the organisation

- What is the “image” of an organisation?

- Why should you adapt the image of your organisation to cultural premises?

- How can you work on your intercultural image?

- Quiz

- External resources

Choosing adequate communication strategies

Just take a minute to reflect: Do you appreciate direct feedback and don’t take it as criticism? Then you belong to the so called “low context cultures” preferring a direct communication style. Do you tend to elaborate constructions when requesting something from your counterpart? Then you may be a member of a culture that appreciates politeness strategies in order not to lose face.

To successfully communicate between cultures it is helpful to remember that there are cultural differences in the application of communication strategies. This can show, for example, in the way cultures express feedback and disagreement but also in the way they negotiate or deliver a presentation (Lüsebrink, 2016, p. 59), or even in different strategies of verbal politeness.

In the following you will learn about some communication skills that may be helpful in intercultural communication.

Adapt your communication style:

In transnational, intercultural communication misunderstandings may arise – independently of language competences – because counterparts may have different communication styles. How openly you tell your counterpart that you don’t agree with him or her is a matter of culture. Some cultures allow their members to verbalise very openly their disagreement and members of these cultures feel comfortable and even appreciate receiving helpful feedback when they have made a mistake. Why is this so?

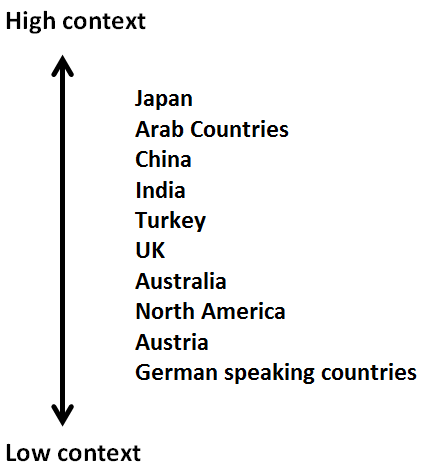

Cultures differ in the degree their members address specific topics in a more or less direct way. So called “Low context cultures” prefer a direct communication style. Members of these cultures rely on the literal meaning of word. “High context cultures” prefer an indirect communication style. In these cultures it is important to read between the lines and to observe non-verbal behaviour in order to grasp the entire meaning of the message.

Here are some characteristics of these communication styles:

| High context cultures (by Edward T. Hall) | Low context cultures (by Edward T. Hall) |

| Covert, implicit messages – many contextual elements help people understand | Overt, explicit messages – little information has to be taken from the context |

| Much non-verbal communication | Less importance of non-verbal communication, more focus on verbal communication |

| Relationships more important than tasks | Task is more important than relationships |

Here is a scale showing the relation of cultures between the poles “high context” and “low context”, a concept developed by Edward T. Hall. The raking is not absolute, as depending on certain topic fields the same culture may have a more or less direct approach to it.

Tips for handling challenging situations in transnational communication

In transnational, intercultural communication it is helpful when you try to adapt your own communication style to that of your communication partners.

Especially when you are in a situation in which you make suggestions, communicate decisions, give instructions or feedback chose carefully your phrases and words.

Try to adapt to the politeness strategies of your counterparts. As member of a low context culture you may be used to less “empty phrases” that have the primary goal of engaging your counterpart in a topic.

Listen actively:

In transnational, intercultural communication misunderstandings may arise – independently of language competences – because the counterparts simply assume they have understood what has been said.

Why don’t they double-check the understanding?

Here are some reasons:

- Trying to really understand the meaning of your counterpart’s words can be hard work. Making assumptions about the meaning is less exhausting because familiar schemes for interpretation can be used.

- Trying to really understand the meaning of your counterpart’s words can be quite time consuming. Making assumptions of the meaning is quicker.

- Trying to really understand the meaning of your counterpart’s words can imply that you may have to modify your opinions. That may be disturbing.

- Trying to really understand the meaning of your counterpart’s words can imply that you can’t say your favourite sentence because it wouldn’t fit to the context. This could mean that you may have to step back and think anew.

However, there may also be cultural reasons that lead to assuming a specific meaning. Depending on the cultural background, having to admit you haven’t understood a statement can mean loss of face for both the recipient of the message and the sender. The recipient feels ashamed of him- or herself and for the counterpart, because he or she causes the inconvenience of making the other reframe the message. The sender may lose face because he or she wasn’t able to be clear enough, causing the other to ask. Certainly this behaviour can be best observed in Asian cultures, like the Chinese. But also in some European cultures, in communication situations where the counterparts have a different status in terms of hierarchy, similar tendencies can be observed.

https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/ton-h%C3%B6ren-mann-ohr-anh%C3%B6rung-musik-159915/

Tips for active listening in transnational communication

- Listen carefully without interrupting your counterpart.

- Observe yourself. Do you feel the need to say something while your counterpart is still speaking? Wait till your counterpart has finished.

- Try to rephrase with your own words what you have understood. If you are worried about making the other lose face, rephrasing may be a way of compromise.

- Try to adopt the perspective of the situation your counterpart has. This helps to understand his or her views.

- Even if your cultural background may not allow for it, try asking questions to understand on the content-level and on the emotional level.

Pay attention to hidden agents

In transnational, intercultural communication misunderstandings may arise – independently of language competences – because counterparts aren’t used to reading hidden messages. These may be transferred by non-verbal elements like gestures, mimic and intonation (for the verbal part see the section above on high and low context cultures) or other meaningful symbols (see also “Challenges in Intercultural communication” [LINK to section above])

Why is it difficult to notice such hidden agents?

Here are some reasons:

- Some cultures may be used more than others to applying hidden agents. Consequently it is easier for them than for others to identify them.

- Even if cultures are used in applying hidden agents those agents may have different meanings (smiling in European and Asian cultures).

- Sometimes it can be a question of personal attitude. There is always a risk to either under- or overestimate meaning in communication and over- or under interpret meaning in communication.

Tips for handling challenging situations in transcultural communication

- Be aware that the volume of voice and speed of speech rate can be culturally determined and can therefore lead to misunderstandings in transcultural communication. To avoid this, observe your communication partners and adapt to their volume and speaking habits.

- Be aware that gestures and gesticulating are also used differently in cultures. Gestures may have a precise meaning in one culture that may be different in another. Also, gesticulating can lead to intercultural misunderstandings. Some cultures which are not used to gesticulating may misunderstand it as a form of emotional display they are not used to.

- Observe if you recognize recurring verbal or non-verbal modes of interaction, like phrases and strategies of politeness, verbal (titles) or material attributes (medals) or any other kind of symbols.

Like learning a new language, transnational intercultural communication is a learning process during which you will notice your own progress by constantly practicing being aware of your own communication habits. This willingness towards enhancing your own potential will make it easier for you to open up for new challenging and interesting intercultural encounters. Try to keep in mind: Wanting to understand your counterpart is an attitude you can acquire.

Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español Français

Français Italiano

Italiano Polski

Polski