[nextpage title=”SHORT DESCRIPTION”]This unit provides three definitions of the term “culture” in relation to the volunteer context. The unit will show how culture can be visualised and it will introduce to the concepts of “cultural dimensions” which represent core elements of cultures. The cultural dimensions will be related to volunteer work and it will be explored where cultural dimensions show and how they can be detected in volunteer work.

[nextpage title=”Quiz”]-

[nextpage title=”What is culture? “]

In recent times the words “culture” and “intercultural communication” are used more and more frequently. We somehow all seem to know what “culture” means when we experience new encounters with people from other countries, nations or ethnic groups. In addition, travelling to other countries and connecting to people from other countries via social media seem to have become a new normality to us all which makes “intercultural communication” seem easy.

But if somebody asked you to define the concept of “culture” could you give a precise definition? And could you say which elements may be relevant in an intercultural encounter?

There are numerous definitions of culture. As early as 1952 Kroeber and Kluckhohn counted over 150 definitions of the term “culture” (Kroeber & Kluckhohn, 1952, p. 291). Here are some of the most popular ones. Culture is…

- …the human-made part of the environment (Harry Triandis, 2002)

- …a collective programming of the mind (Geert Hofstede, 2009),

- …the way in which a group of people solve problems (Fons Trompenaars, 1997)

A definition, which is widely accepted today, understands culture as an “system of orientation” (Thomas, 2010, p. 19), that “allows us to find meaning in the things, people and objects that surround us, as well as in complex processes and the consequences of our behaviour” (Thomas, 2010, p. 20). This orientation system is typical of a specific nation, society, organisation or group. The system defines and influences our perception, our thinking, our values and actions. The system is based on specific symbols (language, gestures, dress-code, greeting conventions etc.) and is passed on from generation to generation, creating a sense of group identity and giving meaning to what we see, perceive and do. The orientation system provides us with behavioural motivators and opportunities but it also sets “conditions and limits” to our behaviour (Thomas, 2010, p. 19).

We could say that this orientation system is our own GPS that helps us to intuitively find our way through the world. For you as a volunteer or a member of a volunteer organisation it can be helpful to have in mind that culture as an orientation system often works on a subconscious basis. We often aren’t aware that culture leads us in our perceptions and judgements. In fact, we can’t avoid perceiving the world around us through our own “cultural glasses”, that means from our own perspective. Especially when you work internationally it is important to develop cultural awareness and sensitivity so to prevent falling into the pitfalls of prejudices, stereotypes and assumptions.

Just take a minute to reflect: Imagine what would happen if you thought people from South Mediterranean Europe are chatty, don’t stick to agreements but friendly. Would these attributes be enough to make you want to develop an international project with them? Maybe not.

Understanding culture and its core elements is a first step towards developing cultural awareness and sensitivity. The concept of culture as an orientation system is still reminiscent of the idea developed in the 18th century – also thanks to the work of Johann Gottfried Herder (1744 – 1803) Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind – that cultures are defined, homogeneous entities each with a common ethnic identity (Löchte, 2005, p. 29f.; Straub et al., 2007, p. 13). For Herder, cultures were limited to a certain territory and cultural contact wasn’t taken into account. Today however the idea of linking one nation to one culture seems rather unrealistic (Welsch, 1999, p. 195).

In fact thinking of volunteers and volunteer organisations wanting to internationalise, talking of homogeneous cultures could seem an anachronism (see also Welsch, 1999, p. 195), especially in our globalised world. In the last years there has been a tendency to perceive “culture” as changeable and interrelated and as something that can’t be clearly distinguished from another. This is why some researchers think that one of the characteristics of these modern societies is a strong orientation towards processes and networking (Bolten, 2013, p. 5). “Culture” in this sense has become a network of reciprocal relationships between people. People are members of more than only one group, i.e. people participate in more than one group-culture. This is why they constantly bring in different elements from other group-cultures into each new group they are in contact with. The result of this process is an ever changing, heterogeneous structure as we can observe it in modern societies. It is difficult to say what is part of our own culture and what is not. This is why some say that cultures are “fuzzy” (Bolten, 2013, p. 6s.).

[nextpage title=”Culture is like an Iceberg”]

https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/eisberg-wasser-blau-ozean-eis-1421411/

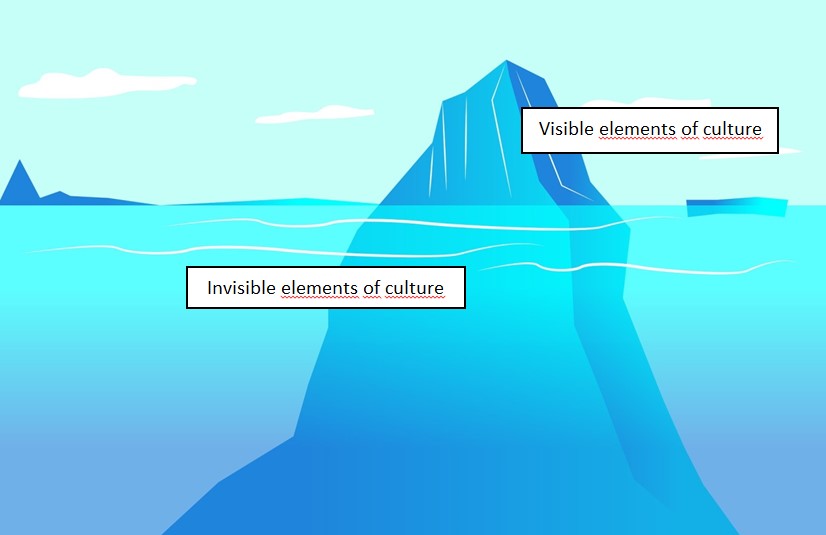

An easy way to represent culture is by imagining that culture is like an iceberg with a visible tip and an invisible part underneath the water surface. The visible tip corresponds to the areas of culture we can see in the physical sense like architecture, dress, food, gestures, devotional practices and much more.

None of the visible elements can ever make real sense without understanding the drivers behind them. It is these invisible, often unconscious elements related to the bottom part of the iceberg which are the underlying causes of what shows on the visible part. So, when thinking about culture, the bottom part of the iceberg will include elements such as religious beliefs, rules of relationships, approach to the family, motivations, tolerance for change, attitudes to rules, communication styles, comfort with risk, the difference between public and private, gender differences and more.

When intercultural conflicts arise people often dispute about the visible representations of cultural elements (Why do Muslim women wear headscarves? Is it right to have a Christian cross in a class-room at school?) – not conscious of the fact that in most cases the values and attitudes behind are the real causes of the conflict.

[nextpage title=”Culture and its core elements”]

Just take a minute to reflect: Imagine for a moment how your volunteer organisation makes important decisions. Do you feel involved in the decision making process?

Depending on the cultural background of your organisation, you may have answered yes or no. This depends on certain elements like the understanding of hierarchy and the manifestation of power of your organisation, for example. Both are relevant elements of the leadership style of your organisation.

There are different tools that help to observe, understand and compare elements of culture. They provide a basis for reflection concerning behaviour which may seem strange to us.

For those working the context of volunteer work the so called cultural dimensions are a suitable basis of reflection when it comes to working in international contexts. Cultural dimensions are based on the hypothesis that there are universal categories of human behaviour common to all cultures but of which cultures show culture-specific manifestations when it comes to find solutions for certain challenges (Layes, 2010, p. 53s.).

The dimensions that serve as a working basis of the Intercultural Communication Module (Module 3) are based on the most important works about cultural dimensions by Geert Hofstede, Fons Trompenaars, Edward T. Hall and The Globe Study.

Interesting to observe is the fact that according to the Globe Study there are country clusters that, when analysed in the working context, show a) similar behaviour and b) similar values, which means that those societies have ideal expectations of how culturally relevant behaviour should be.

Here are some country clusters taken from the Globe Study (https://globeproject.com/results/clusters/middle-east?menu=list#list accessed 21.5.20) that may be relevant for volunteers or volunteer organisations wanting to internationalise:

| Country cluster | Countries |

| Anglo | |

| Eastern Europe | |

| Germanic Europe | |

| Latin Europe | |

| Nordic Europe |

https://pixabay.com/de/illustrations/vernetzung-personen-gruppe-3712818/

Related to the country clusters are certain universal cultural dimensions that have, however, country-specific manifestations. In the following you will find some cultural dimensions taken literally from the Globe Study that may be important for your work (House 2013, p. 12f.). Please keep in mind that the degrees of how strongly or evidently a dimension manifests itself, depends on culture specific factors:

| Dimensions taken from The Globe Study (House, 2013, p. 12f.) | Dimensions in volunteer work /context | Questions for understanding the dimensions in volunteer work |

| Performance orientation: The degree to which a collective encourages and rewards (and should encourage and reward) group members for performance improvement and excellence. | This dimension may show in the way your organisation encourages and supports engagement, training measures and development activities for volunteers in order to enhance their efficiency for a new international project. | How are you rewarded (with immaterial praise, badges “best volunteer of the year”) when you did especially well?

At how many trainings did you participate during the last year? |

| Assertiveness: The degree to which individuals are (and should be) assertive, confrontational, and aggressive in their relationship with others. | This dimension may show in the attitude your organisation or your colleagues have towards measuring achievements among each other and towards bringing forward one’s own interests.

Less competitive cultures lay more importance on relationships and bonding. |

How strongly do you show your desire that your idea be implemented or your objective realized? |

| Future Orientation: The degree to which individuals engage (and should engage) in future oriented behaviours such as planning, investing in the future, and delaying gratification. | This dimension may show, for example, through the effort your volunteer organisation puts in planning meetings or future steps of a project.

|

How much in the future do you plan to harvest the fruits of your work?

How is your monetary spending attitude? |

| Humane Orientation: The degree to which a collective encourages and rewards (and should encourage and reward) individuals for being fair, altruistic, generous, caring, and kind to others. | This dimension may show, for example, in the attitude a society has towards volunteer work. | Is it easy for you as a volunteer organisation to engage people in your activities? Is it easy to do fundraising? |

| Power Distance: The degree to which members of a collective expect (and should expect) power to be distributed equally. | This dimension may show, for example, the extent to which you are accustomed to hierarchical structures in volunteer organisations. It can be also noticed in the way people address their boss or peers. | How do you address your boss – is it like you would address your fellow volunteers? |

| Uncertainty avoidance: The degree to which a society, organization or group relies (and should rely) on social norms, rules, and procedures to alleviate the unpredictability of future events. The greater the desire to avoid uncertainty, the more people seek orderliness, consistency, structure, formal procedures, and laws to cover situations in their daily lives. | This dimension may show, for example, in the complexity of the processes determining the acceptance of new volunteers in an organisation. | How comfortable do you feel with working processes that don’t seem clear to you?

How detailed do you define your working processes? |

In summary: The contents of this unit and in particular the table above may help you to understand some invisible and maybe unconscious elements of your culture. Being aware of the own cultural core elements is a step towards a better understanding of one’s own behavioural reactions. Linked to the country clusters the table may help you to better assess some experience of otherness you can’t explain when in contact with new cultures.

Disclaimer: Of course there is the risk of stereotyping when one tries to attribute what are ‘typical’ behaviours. But one has to keep in mind that cultural dimensions are based on what can be observed and what is normal for most members of a certain culture. It is important to remember to approach another culture not by looking at it through one’s own cultural lens but by observing it neutrally and by postponing judgments.

[nextpage title=”QUIZ”]-

[nextpage title=”EXTERNAL RESOURCES”]

Bolten, J. (2013). Fuzzy Cultures: Konsequenzen eines offenen und mehrwertigen Kulturbegriffs für Konzeptualisierungen interkultureller Personalentwicklungsmaßnahmen, Mondial: Sietar Journal für interkulturelle Perspektiven, pp. 4-10.

Discussion about new perspectives on the term culture

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Books.

Discussion of cultural dimensions

Hofstede, G. and Hofstede G.J. (2009). Die Regeln des sozialen Spiels. In: G. Hofstede and G.J. Hofstede, ed., Lokales Denken, globales Handeln. 4th ed. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, p. 2.

Discussion of cultural dimensions

House, R. J., Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. J. and de Luque, M. S. (2014). Strategic Leadership Across Cultures: GLOBE Study of CEO Leadership Behavior and Effectiveness in 24 Countries. Thousand Oaks / London: Sage.

Discussion of cultural dimensions

Kroeber, A.L. and Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture. A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. New York: Vintage Books, p. 291.

Discussion of the term culture

Layes, G. (2005). Cultural Dimensions. In: A. Thomas, E.-U. Kinast and S. Schroll-Machl, ed., Handbook of Intercultural Communication and Cooperation, vol. 1, 2nd ed. Göttingen: Vanderhoek & Rupprecht, p. 53-64.

Discussion of cultural standards

Löchte, A. (2005). Johann Gottfried Herder. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann.

Discussion of the term culture, also in history

Straub, A. (2007). Kultur. In: J. Straub, A. Weidemann and D. Weidemann, ed., Handbuch interkulturelle Kommunikation und Kompetenz: Grundbegriffe – Theorien – Anwendungsfelder. Stuttgart and Weimar: J.B. Metzler, pp. 7-24.

Discussion of the term culture

Thomas, A. (2010). Culture and Cultural Standards. In: A. Thomas, E.-U. Kinast and S. Schroll-Machl, ed., Handbook of Intercultural Communication and Cooperation, vol.1, 2nd ed. Göttingen: Vanderhoek & Rupprecht, p. 22.

Discussion of cultural standards

Triandis, H. C. (2002). Subjective culture, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2,2 [pdf]. Bellingham: Center for Cross-Cultural Research, Western Washington University, p.3. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1021 [Accessed 10.07.2020].

Discussion of cultural dimensions

Trompenaars, F. (1997). Riding the Waves of Culture. 2. ed. London / Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, p. 6.

Discussion of cultural dimensions

Welsch, W. (1999). Transculturality: The Puzzling Form of Cultures Today. In: M. Featherstone and S. Lash, ed., Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World. London: Sage, pp. 194-213.

Discussion of the concept culture

Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español Français

Français Italiano

Italiano Polski

Polski